The ideas, they live outside

Timeless lessons from nature to awaken your imagination

This email might be too long to read in your inbox.

Click here to read it in your browser.

Hello. I’ve had some quiet months on Substack. Partly due to a busy work period, partly channelling energy into other formats. I’ve also been dealing with some super un-fun legal stuff which has left me with less headspace than I’d like for all things Weirdness Wins.

But at some point the avoidance itself becomes the biggest barrier. It’s like there’s a secret doorway back into the newsletter-writing room in my mind, and each time I walk past it without stepping back inside, it becomes harder to find; hidden behind a thickening Japanese knotweed shroud of endless easy distractions. But here I am, retracing old paths, tearing away the invasive psychic weeds, and getting back to it.

Today’s edition is the penultimate piece in my Creative Renaissance series — a collection of essays exploring the keys to a more creative future; a response to what I discovered when writing Is human creativity fading away?.

So far, we’ve looked at play, chaos, and quiet:

Today, it’s nature’s turn…

A life less urban

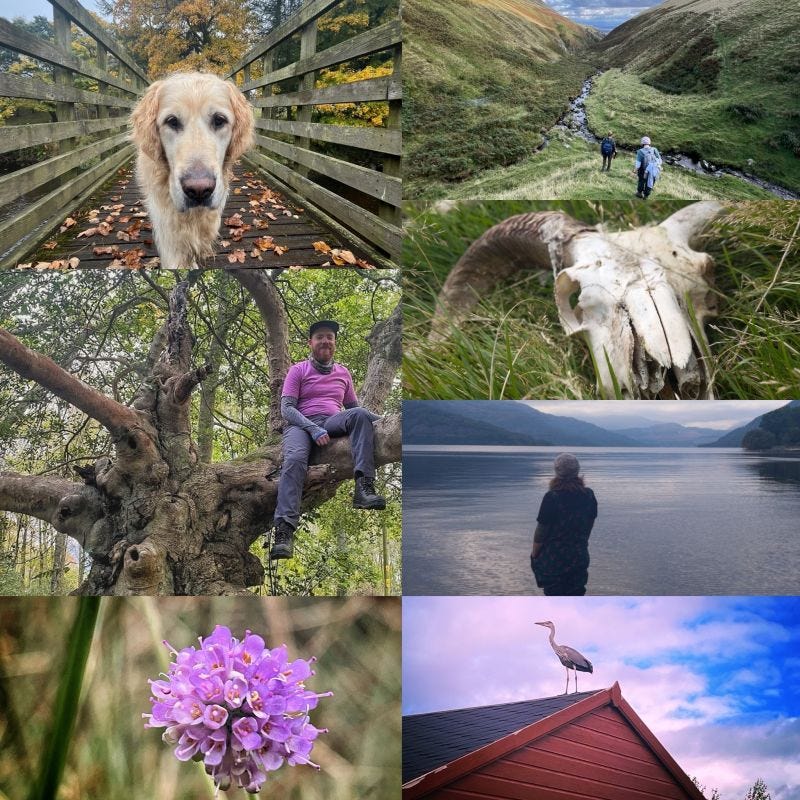

I started thinking properly about this essay last September, when I was living and working in a small rural village in Kinross-shire, eastern Scotland. There were regular visits from red squirrels in our garden. Herons and buzzards keeping us company. Lunchtime walks through lichen-spattered woods and across the River Devon. Left temptingly on a side table in the room where we lit a log fire most nights, there was a copy of Robert Macfarlane’s The Wild Places. And so I watched, listened, wandered, pondered, and read.

That was in the early days of the full-time housesitting adventure I began in August 2025. Today, I’m writing to you from North Wales — outside my window, nothing but cows, fields, trees, hills, and an enormous sunny sky grooved with puffy stratocumulus clouds.

For me and my partner Rhian, the last nine months have been a mostly rural existence (with the exception of some recent European city interludes featuring welcome doses of audiovisual inspo — psytrance in Antwerp, Droog in Amsterdam, Escher in Toulouse, dubby electro-tinged jazz and David Hockney in Paris).

Otherwise, though, we’ve rarely been more than a few steps away from mud and fungus and birdsong. This isn’t how I grew up (in South Manchester suburbia) and it’s not how I’ve lived most of my adult life. I’ve long felt connected to the natural world, but I’ve never been this embedded.

And so it’s in this context, once again away from the rhythms of the city, but still plugged into the internet’s chaos-sockets, that I’m thinking and writing about nature’s role in helping humans operate more imaginatively. Let’s get into it…

Creativity is inherently wild

Sit with the word ‘outside’ for a moment.

Outside is the outdoors. The world beyond walls.

There are also conceptual outsides — political ideas outside the Overton window, scientific ideas outside the current consensus, artistic ideas outside the cages of convention.

This metaphorical connection hints at something deep — the shared wildness of all outsider thinking and the untamed natural world. We can step outside buildings, and we can step outside the established architecture of ideas.

To me, it seems utterly reasonable to imagine that more time in nature — in places of continual exuberant becoming and continual productive decay — might help open us to our wildest, most generative modes of thought. Indeed, versions of this idea have been around for quite some time…

Seeking the sublime

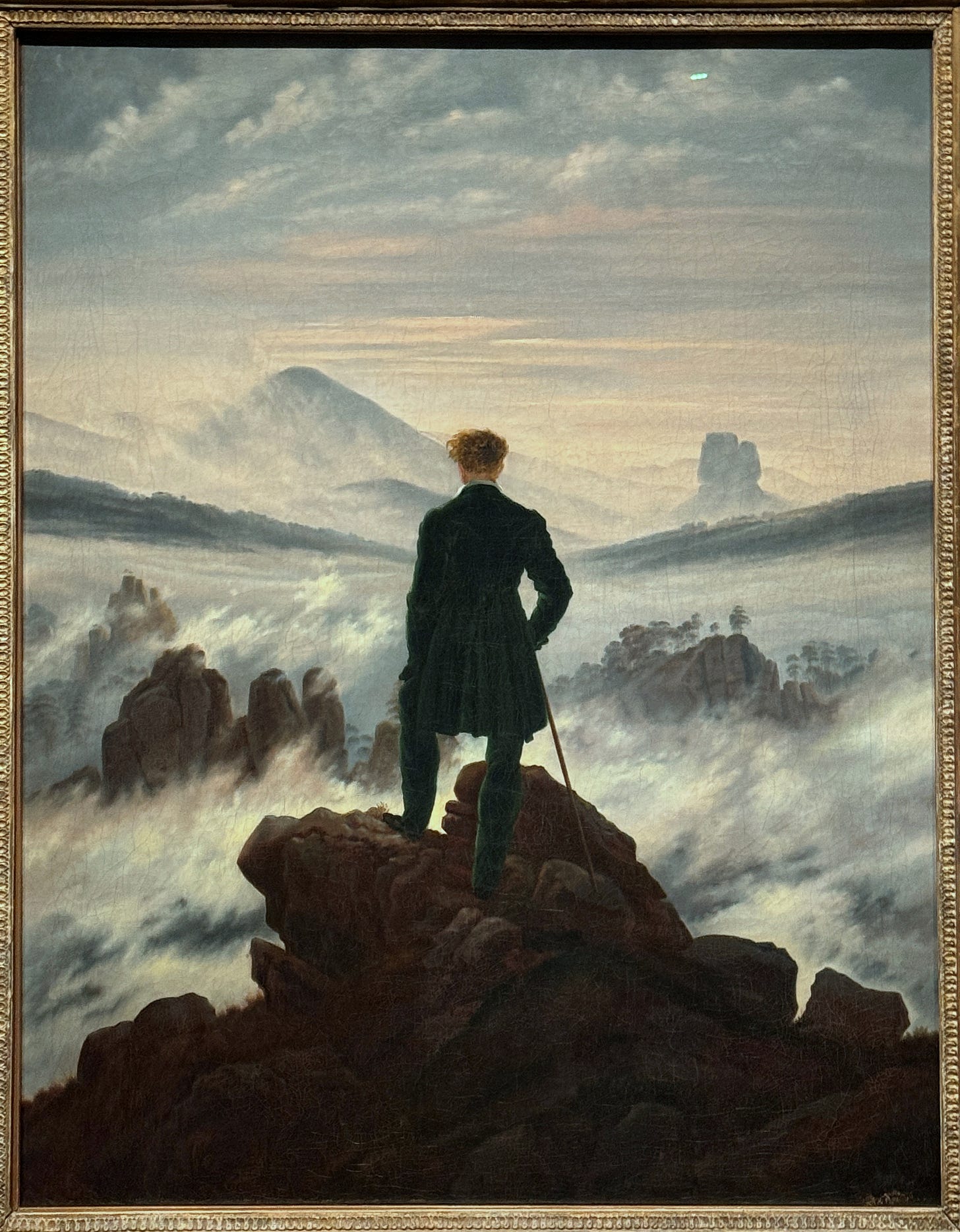

The Romantics, of course, were drawn to nature (especially at its most epic). Mountains, storms, crashing waves and clear starry skies — this stuff inspires awe.

Edmund Burke suggested that these sublime experiences of “delightful horror” and “tranquility tinged with terror” juice up the imagination; they overwhelm the rational mind, making way for feeling, and priming us to create.

Fresh pastures

In 1824, the 22-year-old Ralph Waldo Emerson wrote in his journal that “some kind of intimate relationship with nature's 'fresh pastures' is required for artistic inspiration.” In a line that’s laughably relatable 100 years later, he moaned that people “do not produce new works but admire old ones; are content to leave the fresh pastures awhile, and to chew the cud of thought in the shade.” Arguably, with AI, we’ve invented the ultimate cud-chewing machine.

Henry David Thoreau, Emerson's contemporary and fellow Transcendentalist, spent two years living in the wilderness at Walden Pond, Massachusetts.

“We need the tonic of wildness,” he said, “to wade sometimes in marshes where the bittern and the meadow-hen lurk, and hear the booming of the snipe.” If you’re curious, you can listen to some of the snipe’s amazing sonic output here.

Thoreau believed “the same creative force is also active in human nature, so that even a literary work of art can reasonably be praised as a manifestation of wildness.” For Thoreau, thoughts “spring in man's brain” in the same way that “a plant springs and grows by its own vitality.”

Science catches up

Scientific evidence supporting the relationship between nature and creativity emerged much later. But research has confirmed what these earlier thinkers intuited — that nature exposure enhances creative thinking.

When Abraham Maslow (1908-1970) did clinical studies of people who self-actualised, one thing that set them apart from others was, he wrote, that they lived “more in the real world of nature than in the man-made mass of concepts, abstractions, expectations, beliefs, and stereotypes that most people confuse with the world.” I’m guessing he wouldn’t have been a huge fan of smartphones, social media, or outsourcing our relationships to AI.

A 2015 study of Danish creative professionals found that nature stimulates creativity by sparking curiosity, encouraging new ideas, promoting flexible thinking, and helping individuals recharge their capacity for attention.

Indeed, Attention Restoration Theory (ART), developed by psychologists Rachel and Stephen Kaplan in the 1980s, posits that nature has a particular quality that replenishes our depleted attentional resources. According to a study published in Front Psychiatry in 2022, specific restorative qualities like “being away” (feeling removed from daily life) and a sense of spaciousness were particularly associated with enhanced creativity, especially flexibility (coming up with lots of different ideas) and elaboration (making ideas clearer or richer).

It’s connections all the way down

For biophilosopher Andreas Weber, the connection-forming impulse is a foundational principle of reality. Being in nature reminds us of this fundamental relationality. Walking through a forest, we witness a beautifully complex matrix of relationships. Even if we can’t name all the trees, birds, insects, or fungi, we can feel the interconnected aliveness.

Of all the lifeforms we share this planet with, fungi can perhaps teach us the most about this principle. As Merlin Sheldrake writes in the fantastic Entangled Life:

“Mycelium is ecological connective tissue, the living seam by which much of the world is stitched into relation. In school classrooms children are shown anatomical charts, each depicting different aspects of the human body. One chart reveals the body as a skeleton, another the body as a network of blood vessels, another the nerves, another the muscles. If we made equivalent sets of diagrams to portray ecosystems, one of the layers would show the fungal mycelium that runs through them. We would see sprawling, interlaced webs strung through the soil, through sulfurous sediments hundreds of meters below the surface of the ocean, along coral reefs, through plant and animal bodies both alive and dead.”

A mycelial way of seeing the world helps us internalise two basic overlapping truths about creativity…

1. Creativity is about connecting stuff

The associative theory of creativity, distilled by Sarnoff Mednick in 1962, suggests that creative thinking involves forming new connections between existing ideas.

Thinkers from all kinds of fields have arrived at different versions of this point.

Steve Jobs said “creativity is just connecting things.”

“Originality often consists in linking up ideas whose connection was not previously suspected,” wrote Australian animal pathologist WIB Beveridge in his 1957 book The Art of Scientific Investigation.

Legendary designer Paul Rand believed “the role of the imagination is to create new meanings and to discover connections that, even if obvious, seem to escape detection.”

Vilfredo Pareto, best-known for the 80/20 rule (80% of outcomes result from 20% of inputs), said “an idea is nothing more or less than a combination of old elements.”

And arch idea-stitcher Maria Popova writes that “in order for us to truly create and contribute to the world, we have to be able to connect countless dots, to cross-pollinate ideas from a wealth of disciplines, to combine and recombine these pieces and build new castles.”

Ideas are ecological. They exist in intertwingled webs, in an ever-evolving noosphere.

To do our most creative work, we should seek out the imaginative edgelands where different fields of knowledge intersect. Like ecotones in nature (the places where different habitats merge), these liminal zones are rich sources of novel noetic life.

Also see: Context-mashing.

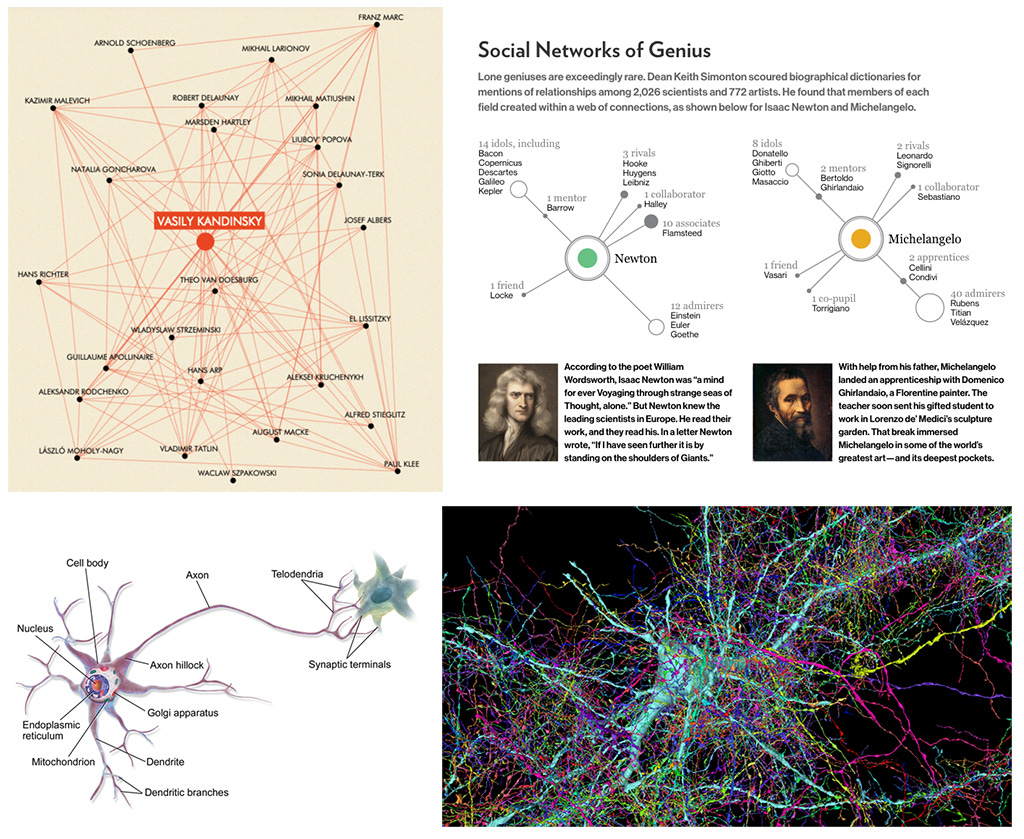

2. Creativity is collective

Even when we’re thinking or working alone, we’re always drawing on, reinterpreting, remixing, and adding to ideas from other minds. Of course it’s all filtered through our own biases, and guided by our unique vision, but creative thinking never happens in a vacuum.

Even our most celebrated “lone genius” figures were deeply embedded in networks of influence and exchange. Einstein's breakthroughs built on work by Lorentz, Poincaré, and others. Newton stood on the shoulders of giants.

Nature is nearer than you think

“There is wildness everywhere, if we only stop in our tracks and look around us.”

Roger Deakin (1943-2006)

“As our eyes grow accustomed to sight they armour themselves against wonder.”

Leonard Cohen (1934-2016)

“The world is full of magic things, patiently waiting for our senses to grow sharper.”

WB Yeats (1865-1939)

Earlier, we talked about nature as a conduit for ego-dampening awe. But there’s a risk that we get stuck thinking of nature as something remote. Thinking we need to experience nature at its most spectacular and dramatic to make it meaningful. When I ran a poll asking how happy people were with the amount of time they spent in nature, 90% said it wasn’t enough. Whilst I don’t disagree that most of us probably spend too much time indoors, getting more contact with nature doesn’t always have to mean straying far from home.

In his search for Britain’s wildest places, Robert Macfarlane came to value, more than ever, “the undiscovered country of the nearby.” Even in cities, we can watch the seasons change, observe spiders building their webs, befriend a nearby tree, or marvel at some wall screw-moss.

As the Irish poet and priest John O’Donohue (1956-2008) wrote:

“What you encounter, recognise or discover depends to a large degree on the quality of your approach. Many of the ancient cultures practiced careful rituals of approach. An encounter of depth and spirit was preceded by careful preparation. When we approach with reverence, great things decide to approach us. Our real life comes to the surface and its light awakens the concealed beauty in things. When we walk on the earth with reverence, beauty will decide to trust us. The rushed heart and arrogant mind lack the gentleness and patience to enter that embrace.”

Here on Substack, Hannah Close also has interesting things to say about reverence and the ‘wild imagination’:

“The wild imagination does not paint a romanticised ‘idyllic nature’, but rather maintains an ongoing dialogue with the real, paying honest attention to the world and reporting back to others so that these lively messages can germinate as seeds of inspiration and renewal in our hearts. The wild imagination knows the difference between romanticism and reverence, reverence being more alive to the sacred found in the everyday.”

We should also remember that we are nature. Our bodies are ecosystems teeming with microorganisms, our breath part of the planet's carbon cycle, our cells powered by the same processes that energise all life. Connecting with nature isn't about reaching for something alien, but about awakening to what we are.

It can’t always be spring

Dunno about you, but I LOVE this time of year. In spring, the infant’s way of experiencing the world as, in William James’ words, a “great blooming, buzzing confusion” feels a little easier to access.

We welcomed the season in a sleepy mountain village in the south of France, backing onto woodland blooming and buzzing with butterflies and hares and lizards and snakes and stoats. And we returned to the UK at its most green and pleasant, ferns unfurling, birds returning, and flowering hawthorn-filled landscapes that seem freshly doused with champagne, as David Hockney once observed.

It’s probably no coincidence that this is the moment I’m re-entering the newsletter groove. It’s almost impossible not to create surrounded by all this renewal, all this possibility.

But what about the murkier, mulchier seasons? There’s wisdom in the winter, lessons in the reddening of the leaves. These processes remind us that withdrawing, resting, and metabolising what came before are natural and necessary phases in the creative cycles of life.

Just as the forest floor needs its carpet of decay, our subconscious soil needs time to compost ideas so they can fertilise future work. There’s a world of noisy voices out there telling you that prolificness is the ultimate virtue, but nature reminds us that fallow times needn’t be a source of guilt. Indeed, they might be the precondition for our most radical imaginative leaps.

That’s it for today. Stay tuned for more Curated Chaos soon, and look out for the final essay in this series (on psychedelics, meditation, and other apps for the mind).

Wear your weirdness with pride

You can now buy official Weirdness Wins tees on Teemill. There are a few designs to choose from, but this one’s my fave:

Side project shout-out

Fully Saturated™ is a new report by me and Emily Penny, offering an in-depth look at how UK design agencies position themselves.

If you work in this sector, it’ll help you understand the competition like never before.

Discover the latest positioning trends

Know the messaging clichés to avoid

See how you compare to the UK’s standout studios

Work with me

Curious about working together? I help interesting people and brands with words, workshops, and weird ideas.

Check out the Chaos & Co site or reply to this email if you’d like to know more.